Developments in the Management of Bladder Cancer

Developing personalised, patient-specific treatment (by the Museum staff)

From open implantation of radioactive implants, hazardous for patient & surgeon, to minimally-invasive bladder removal & targeted treatment

In 1895, Ludwig Rehn used a cystoscope to identify bladder cancer in 3 of 45 workers at a dye factory in Frankfurt. This was the first indication that exposure to aromatic amines (in particular, beta-naphthylamine & 4-amino-diphenyl) during the dye-making process may cause bladder cancer.

His discovery had a significant impact on urology and occupational health, leading to screening and preventive measures in industries where workers are at risk; thanks to Ludwig Rehn, these measures remain in place today.

Tumourigenesis in Bladder Cancer

In the UK, both TH Wignall (1929) and JB MacAlpine (1929) published accounts of bladder tumours which had occurred in workers in aniline dye factories. MacAlpine laid stress on the occurrence of cystitis prior to presentation and reported that cystoscopically the bladder showed a bright erythema. Denis Poole-Wilson, who was taught by them took over the practice of McAlpine in Salford and contiuned this work into the 1950s and 60s. He championed the "wet smear" urine test (introduced by Papanicoloau in 1951) to screen chemical factory workers.

Many industrial carcinogens have now been identified. Bladder cancer was recognised officially as an industrial disease (Prescribed Industrial Disease No.39) in 1962 which occurred most commonly in the manufacture of dyestuffs, in the rubber and electric cable industries (generally before 1950), and in the retort houses of gasworks producing coal gas. Following appropriate national legislation the incidence of bladder cancer in these industries. However, the single most important risk factor for developing bladder cancer (and later tumour recurrence) is, of course, cigarette smoking. Carcinogens in tobacco smoke are filtered by the kidneys and damage urothelial DNA, most commonly in the bladder but also, less often, in the kidneys and ureters. Stopping smoking reduces the risk of developing bladder cancer by about 30% after 5 years of cessation, but the risk never returns to normal for those who do stop smoking.

Over the years, it has also been shown that pelvic irradiation, chronic schistosomiasis, chronic UTIs and cyclophosphamide treatment can cause bladder cancer. Although bladder cancer does not typically run in families, large population studies have identified many gene variants that slightly increase the risk of bladder cancer. Specific conditions that may be linked to a risk of bladder cancer are:

- retinoblastoma - mutations of the RB1 gene;

- Cowden syndrome - mutations of the PTEN gene; and

- Lynch syndrome - mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes (e.g. MHL1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2).

Diagnosis & Staging

In the mid-20th century, bladder tumours were diagnosed endoscopically and treated by resection or fulguration (probes shown above left). followed by a regime of "check cystoscopies". Early bulb cystoscopes did not have very clear views and often papillary tumours were removed through open cystotomy. Special forceps (above right) were introduced by JD Fergussen in 1949 to grasp tumours whilst excising them with hand-held diathermy points.

Interstitial irradiation, delivered using gold grains or iridium wires, was sometimes performed using open surgery; the radiation dose to both patient and surgeon was significant and poorly controlled !

Interstitial irradiation, delivered using gold grains or iridium wires, was sometimes performed using open surgery; the radiation dose to both patient and surgeon was significant and poorly controlled !

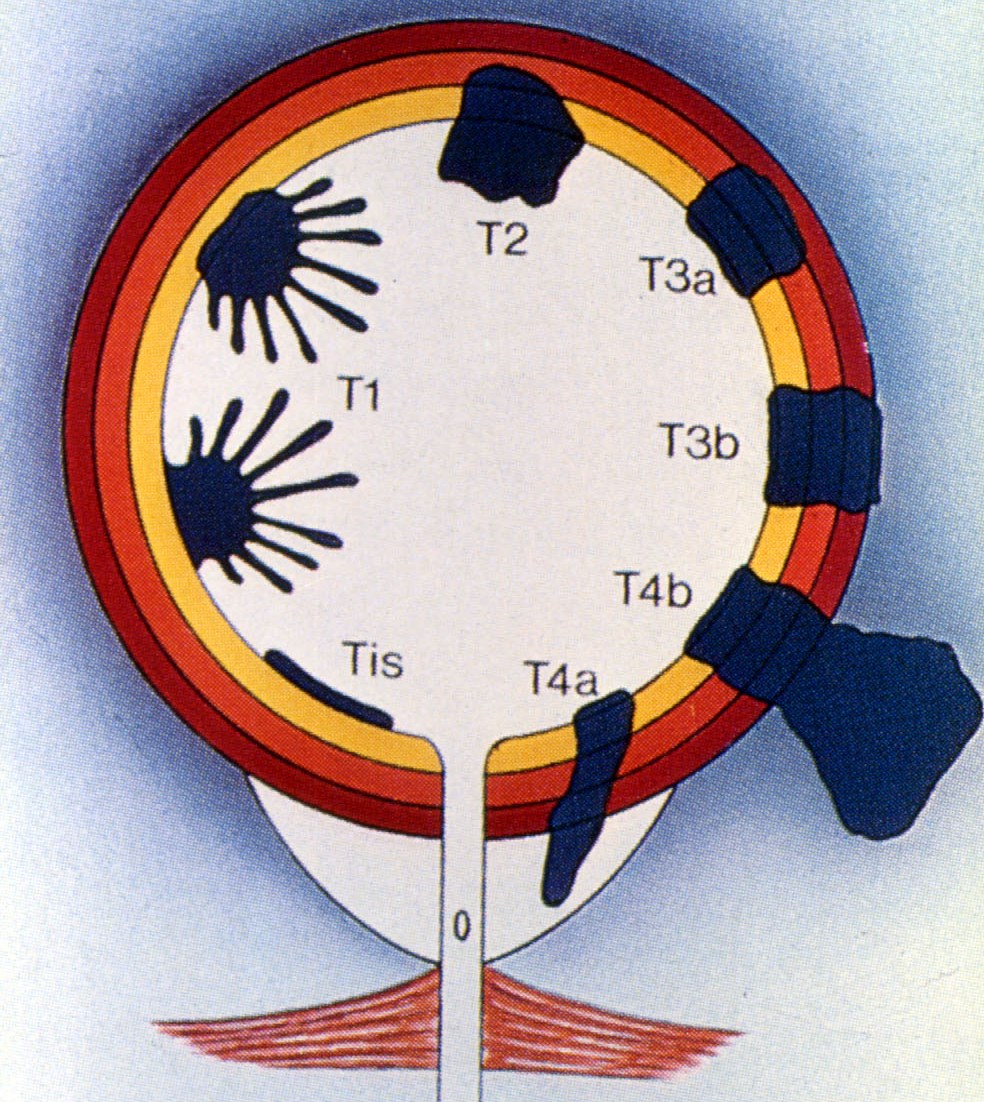

What rationalised the management of bladder cancer was a protocol for bladder cancer that allowed more specific treatment based on tumour stage & grade. This became mainstream with the introduction of TNM staging (T-staging pictured right). Following previous work by Prof Pierre Denoix, the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC) introduced the international TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours in 1953 based upon which the American Joint Committee for cancer staging published the first Clinical Staging for Carcinomas of the Urinary Bladder in 1967. This was modified by the UICC in 1974 and is now in its 9th edition. This greatly improved prediction of prognosis.

The presence of muscle invasion has usually been determined by the finding of tumour in deep muscle biopsies from the base of any tumour. These biopsies are usually done after initial resection of the exophytic tumour but, in recent years, some clinicians have been removing tumours en bloc using dissection with electrocautery or, most recently, laser energy. This is thought to produce a more accurate picture of the cancer stage.

Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer (NMIBC)

The "game-changer" for NMIBC was the introduction of intravesical instillations of cytotoxic agents. The first of these was Thiotepa synthesised in 1953 and shown to be effective against superficial bladder tumours by British urologists HC Jones and JS Swinney. Subsequent European and British trials showed that Adriamycin, Epirubicin and Mytomycin C were also effective against small NMIBC and reduced the frequency of local recurrence.

Recognition of high-grade disease

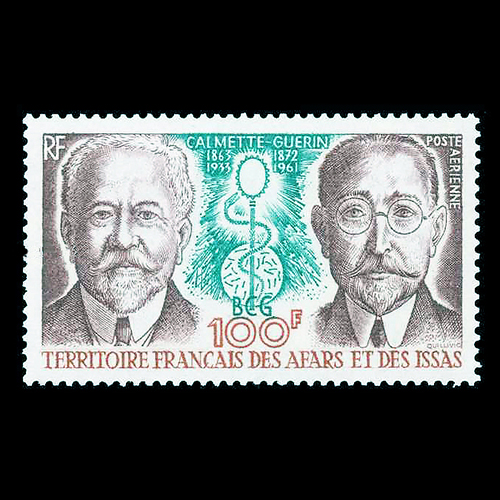

In the 1990s, it was recognised that high-grade superficial bladder cancer (and some cases of carcinoma-in-situ) had the potential to progress to muscle invasion despite our best efforts. For these patients, intravesical instillations of Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), given intermittently over several weeks, minimised the risk of progression to invasive disease. Unfortunately, despite treatment with BCG, a small sub-group of these patients would eventually progress to MIBC (see below).

The concept of an "unstable epithelium", in which abnormal, flat, malignant patches in the bladder of carcinoma in situ could easily be overlooked on conventional cystoscopy was highlighted by pathologist RO Schade and JS Swinney in 1968. Much more recently the use of techniques such as hexaminolaevulinate immunofluorescence to reveal these areas under blue light cystoscopy, introduced in the early 2000s, has helped to identify previously unrecognised abnormal urothelium.

The concept of an "unstable epithelium", in which abnormal, flat, malignant patches in the bladder of carcinoma in situ could easily be overlooked on conventional cystoscopy was highlighted by pathologist RO Schade and JS Swinney in 1968. Much more recently the use of techniques such as hexaminolaevulinate immunofluorescence to reveal these areas under blue light cystoscopy, introduced in the early 2000s, has helped to identify previously unrecognised abnormal urothelium.

Follow-up by cytology & cystoscopy

Various biochemical tests to detect malignancy in the bladder have been used over the years, primarily to direct endoscopic resources towards those patients under long-term follow-up who may have tumour recurrences. However, all these tests suffer from false negatives (and positives) and conventional urine cytological examination by an experienced pathologist seems to be just as accurate.

Repeated cystoscopy over a period of years remains the mainstay of follow-up for patients with NMIBC. However, the introduction of the flexible cystosope, without the need for general anaesthesia, dramatically changed the landscape for these patients. Instead of coming into hospital for a general anaesthetic with an overnight stay, they could attend a clinic or day unit for their procedure under local anaesthetic. For a brief period in the late 1980s, Nd-YAG laser cautery under local anaesthetic, at the time of flexible check cystoscopy, was used in some centres to cauterise recurrences. This approach has recently resurfaced with the TULA (transurethral laser ablation) technique.

Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer (MIBC)

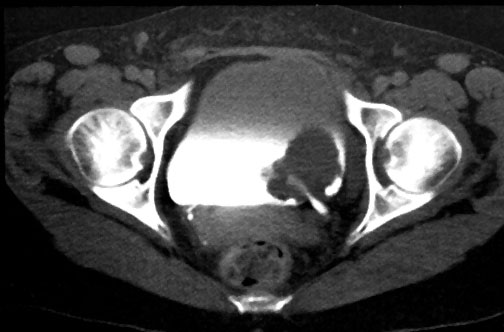

In the early years of BAUS, bladder cancer that was muscle-invasive at diagnosis (right) treatment options were partial cystectomy, total cystectomy or radiotherapy. Operative morbidity and mortality were high and disease recurrence frequent. The presence of muscle invasion was determined by … biopsies from the base of the tumour and by bimanual palpation under anaesthesia. Radiotherapy had been championed in England at the Middlesex Hospital by radiotherapist Sir Brian Windeyer and Clifford Morson, who would become the second President of BAUS in 1947.

In the early years of BAUS, bladder cancer that was muscle-invasive at diagnosis (right) treatment options were partial cystectomy, total cystectomy or radiotherapy. Operative morbidity and mortality were high and disease recurrence frequent. The presence of muscle invasion was determined by … biopsies from the base of the tumour and by bimanual palpation under anaesthesia. Radiotherapy had been championed in England at the Middlesex Hospital by radiotherapist Sir Brian Windeyer and Clifford Morson, who would become the second President of BAUS in 1947.

The alternative, total cystectomy, was first performed by Bernhard Bardenheuer in 1887 in Koln, Germany. It was in use in North America in the 1920s and 1930s, and in some British urology departments since the early 1950s.

The relative merits of radiotherapy and radical cystectomy were debated and only partially clarified by urologist David Wallace and radiotherapist Julian Boom, both at the Royal Marsden Hospital, who conducted a randomised trial that compared radiotherapy alone with cystectomy preceded by neoadjuvant radiotherapy. The outcome favoured the combined treatment and this was increasingly adopted in the UK but longer experience revealed higher post-operative morbidity and mortality, and pre-operative radiotherapy has been discontinued.

Chemotherapy

The first use of systemic chemotherapy for advanced bladder cancer was by Prout and colleagues (Massachussetts) in an unsuccessful trial of 5-Fluorouracil in 1968. The second was a phase II trial of Methotrexate at the Royal Marsden Hospital in 1971. This demonstrated sufficient activity to warrant further development in Newcastle but it was Cisplatin, introduced in 1978 that showed greater promise, particularly when combined with methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin & cisplatin (MVAC). Subsequent combination of Cisplatin with Gemcitabine (GemCis,2000) was less toxic but demonstrated similar efficacy, both regimens being options currently. Latest research suggests encouraging efficacy with Enfortumab vendolin with pembrolizumab (EVP) but truly effective systemic therapy for advanced bladder cancer remains elusive.

Surgery

Although the first cystectomy for bladder cancer was performed in 1887, techniques for invasive cancer have been refined over the years to include removal of the surrounding tissues (radical cystectomy) ± local lymph nodes.

Over the last 40 years, British urologists have edged towards radical cystectomy, in combination with chemotherapy, as the standard treatment for MIBC. Inevitably, this meant that some form of urinary diversion was needed. Urinary diversion into the sigmoid colon (ureterosigmoidostomy) was an early procedure of choice, but it caused major metabolic upsets, urinary incontinence per rectum, derterioration in renal function and, in the long-term, predisposed to the development of colonic tumours where the ureters join the sigmoid colon.

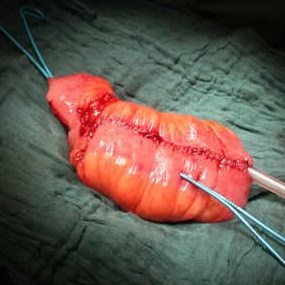

As a result, the ileal conduit, devised by Bricker (USA) in 1950,became the diversion of choice for urinary diversion after cystectomy. From the 1980s onwards, however, construction of a neobladder became the aim for some surgeons, and a plethora of bladder substitutes were described, all with different features but all using intestinal segments to create a new bladder (pictured right) that could be anastomosed to the membranous urethra. It used to be said that, at one point, almost every state or institution in the USA had a type of neobladder named after it!

As a result, the ileal conduit, devised by Bricker (USA) in 1950,became the diversion of choice for urinary diversion after cystectomy. From the 1980s onwards, however, construction of a neobladder became the aim for some surgeons, and a plethora of bladder substitutes were described, all with different features but all using intestinal segments to create a new bladder (pictured right) that could be anastomosed to the membranous urethra. It used to be said that, at one point, almost every state or institution in the USA had a type of neobladder named after it!

Catheterisable valved conduits (e.g. the Kock continent ileal reservoir) were also devised, using segments of bowel fashioned into a continent pouch; these meant that the patient was not permanently incontinent into a drainage bag but used a catheter passed through the abdominal wall to empty the conduit intermittently. The main problm with continent conduits, however, has always been failure or malfunction of the valve mechanism, resulting in the need for surgical revision.

The "game-changer" for MIBC has undoubltedly been the introduction of robotic-assisted technology and minimally-invasive techniques for radical cystectomy and urinary diversion/neobladder formation. It is now possible to perform the entire procedure intracorporally using robotic assistance, with a huge improvement in morbidity & recovery time for the patient.

As time has passed the treatment of MIBC has come a full circle, and the focus is now on bladder preservation where possible (see below).

National and International Clinical Research.

One of the most important contributions to the development of bladder cancer treatment by British urologists has been their work with the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC).

Professor Henri Tagnon from the Institut Jules Bordet, Paris, established what became the EORTC in 1962, introducing the concept of randomised trials for cancer in Europe. In 1973 discussion with Philip Smith (Leeds) led to the formation of a prostate trials group and, in 1976, a similar group for bladder cancer. This collaboration of European and British urologists, principally from Yorkshire, became the GenitoUrinary Group of the EORTC, subsequently led for significant periods by Philip Smith, Brian Richards (York), Donald Newling (Hull) and Reg Hall (Newcastle).

In 1981 the British Medical Research Council established a Working Party for Urological Cancers under the chairmanship of Brian Richards, joined by Smith, Melvin Robinson (Pontefract), Robin Glashan (Huddersfield), David Kirk (Glasgow), Newling, Hall, leading oncologists, and statisticians Laurence Freedman and Mahesh Parmar. The purpose was to undertake national clinical trials of treatment for bladder, prostate, kidney and testis cancer. It is the outcome of these trials and collaboration with the EORTC that form the basis of current treatments for bladder cancer.

Emerging Therapies

The main improvement in prognosis in the 21st century is inextricably linked to the introduction of multi-disciplinary care, where urologists, oncologists and radiotherapists all work together to provide individualised care for the patient. As a result of this, there is now an increasing interest in bladder-preserving approaches (i.e. TURBT plus chemotherapy & radiation) with the aim of achieving similar outcomes to radical cystectomy with less morbidity.

Other innovations that are expected to improve prognosis are:

- advances in immunotherapy - e.g. systemic pembrolizumab for BCG-unresponive carcinoma in situ;

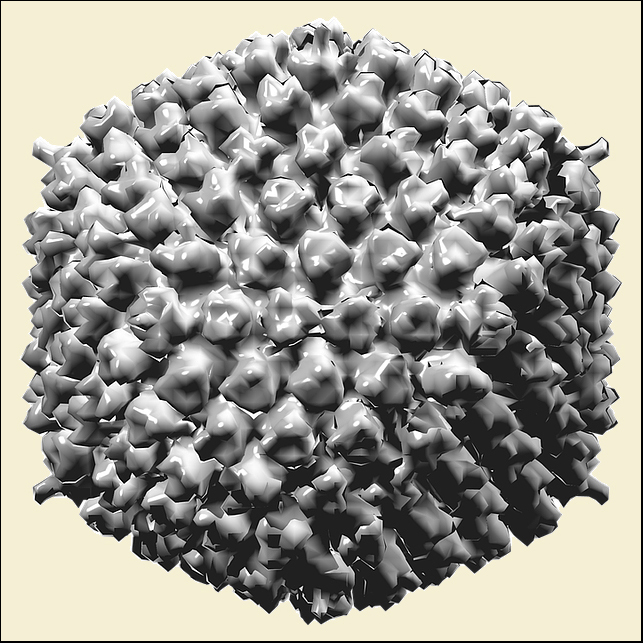

- oncolytic viruses - such as adenovirus CG0070;

- recombinant adenovirus interferon-alpha-2b;

- molecular targets for therapy;

- new diagnostic tools - such as immunofluorescence with "blue-light" cystoscopy;

- the EORTC STARBURST project - aims to validate MRI+biomarkers as predictors of the response to neoadjuvant therapy, opening the door to personalised, bladder-sparing strategies (read more).; and

- improved combination chemotherapy for metaststic cancer - the combination of enfortumab vedotin (a chemotherpay agent) & pembrolizumab (immunotherapy) doubles survival rates, with a decreased risk of disease progression and fewer side-effects than conventional therapy;

So much has changed in the last 80 years that it seems impossible to predict where we will be in 80 years' time - generally, though, the consensus seems to be that molecular biologists, not surgeons, will lead in the search for a cancer cure

Additional information

Click on any image below to access more detailed information about items & individuals featured above, or click here to go to the main History section of BAUS Virtual Museum for more general history content:

|

Ludwig Rehn

|

Edwin Beer

|

UICC

|

|

Dennis Poole-Wilson

|

BCG

|

Flexible cystoscopes

|

|

NIls Kock

|

Neobladders

|

Oncolytic viruses

|

|

|

|

|

← Back to BAUS 80th Anniversary