A history on cuneiforms

Mesopotamia is the region between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, made up of modern-day Iraq, Kuwait and Syria together with segments of the Iraq-Iran and Turkey-Syria border areas. This fertile land, cultivated for over 10,000 years, has been called the "Cradle of Civilisation" and was the location of Babylon.

Mesopotamia is the region between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, made up of modern-day Iraq, Kuwait and Syria together with segments of the Iraq-Iran and Turkey-Syria border areas. This fertile land, cultivated for over 10,000 years, has been called the "Cradle of Civilisation" and was the location of Babylon.

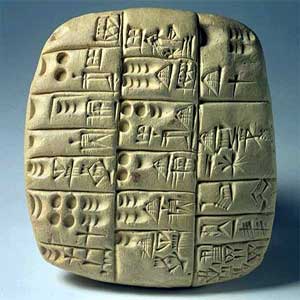

Most of our knowledge of ancient Mesopotamian medicine comes from the interpretation of cuneiform tablets (pictured). This method of inscribing clay tablets with a "wedge" and then baking the clay to preserve the text is one of the oldest forms of writing. The cuneiform records suggest a sophisticated and long-established tradition of experimentation and treatment using plant, animal and mineral extracts.

The largest surviving medical text from the period is the "Treatise of Medical Diagnosis and Prognosis". This comprised 40 tablets and was organised into anatomical sections with specialty sub-sections. The Code of Hammurabi outlined the law in general but, specifically, defined the principles of medical ethics, fee scales for physicians and the penalties for bad treatment.

Read more about the Code of Hammurabi

Mesopotamian medicine men

There were three main types of clinician:

- baru (the diviner) - who made diagnoses and gave a prognosis;

- asipu (the magician) - who drove out evil spirits using rituals & incantations; also examined animal livers (known as hepatoscopy) to diagnose and determine treatment, since it was believed that the liver was the "controller" of bodily function; and

- asu (the healer) - who used both charms and medications to relieve symptoms.

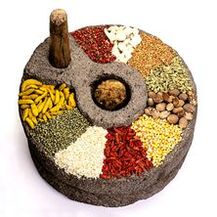

Most attempts at healing involved a combination of religious ritual and physical treatment, with the three types of clinicians working together. More than 250 medicinal plants (a selection pictured, right), 120 mineral extracts and 180 other substances were documented as being used for treatment, often prepared in the patient's home, and administered by a relative on the advice of the asu.

Most attempts at healing involved a combination of religious ritual and physical treatment, with the three types of clinicians working together. More than 250 medicinal plants (a selection pictured, right), 120 mineral extracts and 180 other substances were documented as being used for treatment, often prepared in the patient's home, and administered by a relative on the advice of the asu.

Surgery, urology & sexology

The risks of surgery were high and the penalties for mishaps severe. Anatomical knowledge was poor and generally obtained from sacrificed animals, largely because of the taboos surrounding dissection of human corpses. However, four cuneiform tablets have been found which describe surgical procedures: one was too fragmented to be deciphered, the others described drainage of an empyema (pleural abscess), an operation on the skull, and the post-operative care of surgical wounds.

Scalpels were used primarily to lance boils and for blood-letting. No osteological (bone) evidence has been found for trephining of the skull and routine circumcision was not practised in Mesopotamia (although it was in other areas of the Middle East).

Some texts describe the pain and bleeding caused by passing kidney or bladder stones for which powerful agents such as opium and cannabis were used. Others mention incontinence of urine for which treatment recommendations included introducing medications into the urethra through a bronze catheter.

Some texts describe the pain and bleeding caused by passing kidney or bladder stones for which powerful agents such as opium and cannabis were used. Others mention incontinence of urine for which treatment recommendations included introducing medications into the urethra through a bronze catheter.

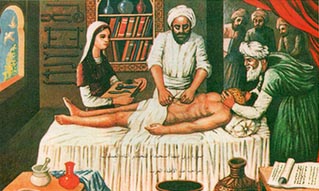

The asipu may also have acted as sex therapists for both sexes, using incantations and massage of oils (pictured), sometimes augmented with iron extracts, into the genital areas. For erectile dysfunction (impotence), the medical texts also recommended:

If a man loses his potency, you dry and crush a male bat that is ready to mate, you put it in water which has sat out on the roof and you give it him to drink; the man will then recover his potency …

The final word ...

The foundations of Mesopotamian medicine were lost with the decline of Babylon. Despite the extensive pharmacopoeia and well-researched, well-documented practices, their techniques were largely abandoned and it fell to the ancient Egyptians to "rationalise" medical procedures. Their ideas were then adopted and further modified by Hippocrates and the ancient Greek physicians. As a result, the contribution of Mesopotamian medicine to current practice has largely been forgotten.

← Back to Time Corridor