Popularised by Hugh Hampton Young

Carcinoma of the prostate is the commonest cancer in men in the UK with 30,000 new cases each year and 10,000 deaths.

For many years, British urologists resisted the urge to copy their transatlantic colleagues by carrying out extirpative surgery for prostate cancer, largely because disease detection was often too late to permit "cure".

A gradual "sea change" over the last 20 years has seen the introduction of radical prostatectomy for early prostate cancer in the UK and now, between 1500 and 2000 radical prostatectomies are performed each year.

What may appear to many to be a modern procedure, however, had its origins in the early years of the last century.

The First Radical Prostatectomy

The Surgeon

Hugh Hampton Young (18 Sep 1870 - 23 Aug 1945) is generally regarded as the father of American Urology. He was born in San Antonio, Texas, studied medicine at the University of Virginia but went to Baltimore in 1895 to undertake postgraduate work at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. In 1898, Young became head of genitourinary surgery at Johns Hopkins. He was instrumental in the founding of the Brady Urological Institute which he directed from its founding in 1915 until his retirement in 1942.

The Patient

All that is known of the patient is that he was a 70 year old married preacher. He presented to Young on the 1 April 1904 with an eleven-month history of urethral pain which had progressed to the thighs and perineum. He had tried a long course of unhelpful osteopathic treatment (prostatic massage) and had undergone a Bossini’s electrocautery operation (an early form of TURP) on his prostate four months previously. Rectal examination revealed an enlarged, irregular, nodular and hard gland. Young felt that the prostate had not progressed beyond the capsule; however, the left seminal vesicle was also hardened. He had a 400ml residual urine.

The Operation

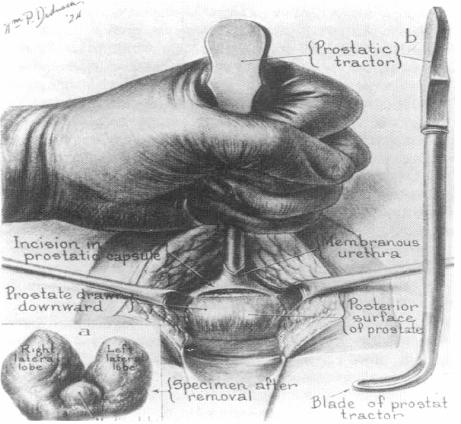

The operation was carried out on 7 April 1904; Young was assisted by his chief, William S. Halstead. With the patient in lithotomy, a curved perineal incision was made above the anus. The plane between the rectum and anus was developed by blunt dissection. The urethra was opened, a prostatic retractor passed into the bladder, and used to pull down the gland, intact with its capsule. This enabled the bladder to be opened above the prostate and then the prostate could be detached from the bladder and urethra. The vasa and seminal vesicles could be visualised and removed with the gland. The open bladder neck was then sutured to the urethra using silk (he later recognised that use of this material was a major mistake). A rubber bladder tube was passed and secured to the urethra and the wound was closed with drainage.

The patient, according to Young, had a “smooth convalescence”. The patient was walking at two weeks. A small perineal urinary fistula dried up by day 16 and he was discharged voiding normally on day 23. Although he was dry at night, he dribbled urine during the day; this improved over the next five months.

In October 1904, he represented with urethral pain and increasing incontinence. Young was unable to pass a silver catheter but managed with a smaller filiform bougie. After dilatation, he sounded a stone. On cystoscopy, there were three; one was attached to a silk suture. On the 23 December 1904, the stones were crushed by litholapaxy and the suture was pulled out. Sadly, the patient died one month later of sepsis.

Discussion

This was the first radical operation carried out for carcinoma of the prostate with the intent of cure. Young’s chief at Johns Hopkins was William S Halstead who devised the radical mastectomy for breast cancer. It is easy to see the hope of these men that excision of the prostate and capsule may provide a cure for localised prostate cancer.

Clinically, with the invasion of the seminal vesicle, the preacher’s prostate cancer would have been T3c and we now know that this would give him only a 25% chance of PSA-free survival (Harris 2003). The histology, however, showed that the disease was invading the bladder (T4) and was still present in this area at post-mortem.

The patient, however, was symptomatically improved for eight months. The cause of his recurring symptoms and eventual demise was due to a poor choice of suture material which Young recognised and corrected; in subsequent cases, he used catgut (which was too short-lasting) and, later, silkworm gut.

The majority of radical prostatectomies are now carried out retropubically but Young’s operation is still used. Its advantages are:

- a small, hidden incision for better cosmesis

- less post operative pain with faster convalescence, return to work and strenuous activities

- fewer adverse cardiovascular effects because fluid shifts are reduced

- less blood loss

- shorter operative time and length of hospitalization

- an excellent posterior exposure to limit positive margins posteriorly, laterally, and apically

- a precise watertight anastomosis performed under direct vision

- better visualization of the prostatic apex, facilitating avoidance of positive apical margins, easing the sparing of neurovascular bundles, and improving visualization of the membranous urethra.

It also avoids scar tissue from previous abdominal surgery and is easier for patients who are obese.

Bibliography

Young HH. Cancer of the prostate, a clinical, pathological and post-operative analysis of 111 cases.

Annals of Surgery, 1909; 50(6): 1144

Hugh Young: A Surgeon's Autobiography. New York, Harcourt, Brace and Company (1940).

Young HH: The Early Diagnosis and Radical Cure of Carcinoma of the Prostate.

Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital 1905;VXVI:315-21

AR Ramsden, R Thurairaja, R Persad, GW Chodak. Current trends in the management of radical retropubic prostatectomy: is short-stay RRP feasible in the United Kingdom?

Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases 2004; 7(1): 50

Harris MJ. Radical perineal prostatectomy: cost efficient, outcome effective, minimally invasive prostate cancer management.

Eur Urol 2003; 44(3): 303

← Back to Prostate