William Harvey to Antonie van Leeuwenhoek

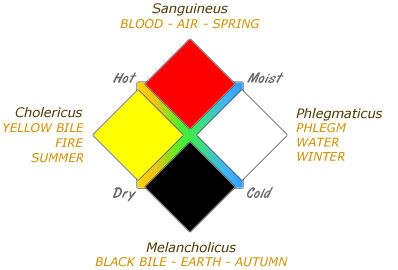

17th century medicine was, unfortunately, still handicapped by wrong ideas about the human body. Most doctors still thought that there were four fluids (or "humors") in the body (pictured right): blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile and illness was believed to result from an excess of one humor.

17th century medicine was, unfortunately, still handicapped by wrong ideas about the human body. Most doctors still thought that there were four fluids (or "humors") in the body (pictured right): blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile and illness was believed to result from an excess of one humor.

However, during the 17th century, a more scientific approach to medicine emerged and some doctors began to question these traditional ideas. For example, physicians followed the practises of indigenous natives and discovered that malaria could be cured with bark from the cinchona tree (effective because, as we now know, it contains quinine); the cause of malaria (a parasite) and its vector (a mosquito), however, were to remain undiscovered until 1880.

If you visited a physician in the 17th century, many of the treatments provided would be based on superstition and personal dogma. The treatments offered might include:

If you visited a physician in the 17th century, many of the treatments provided would be based on superstition and personal dogma. The treatments offered might include:

- leeches (pictured) - commononly used (and still occasionally employed today);

- maggots - to remove dead flesh (still in use today);

- mice - to cure problems such as gout, earache and even to clean teeth;

- ferrets & woodlice - in the treatment of whooping cough;

- spiders' webs - used to stop nosebleeds, heal wounds and draw out poison (swallowing a spider was thought to cure a fever); and

- oil of cloves - to draw out worms thought to cause toothache (if this failed, the tooth was extracted).

Medicine did, however, continue its slow advance, starting with the invention by Santorio Santorio , an Italian, of the "thermoscope", an early type of medical thermometer with a visual scale.

Scientific discovery

In 1628, William Harvey published his thesis on how blood circulates around the body. Like so many scientific advances through the centuries, this flew in the face of all the theories prevalent at the time and caused much controversy. It was many years before his theory gained general acceptance.

Apart from Harvey, the most famous English doctor of the 17th century was Thomas Sydenham (1624-1689, pictured). He is sometimes called the "English Hippocrates" because he emphasized the importance of carefully observing patients and their symptoms.

Thomas Sydenham

Medicine was also helped by the microscope, invented at the end of the 16th century. Robert Hooke was the first person to describe cells in his book "Micrographia", published in 1665. However, in 1683, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek managed to see individual red blood cells and also identified bacteria under the microscope (although he did not appreciate their significance).

Robert Hooke Antonie van Leeuwenhoek

Surgery and urology

Surgery in the 17th century was still fairly crude. Barber-surgeons treated wounds and performed amputations without anaesthetic, using instruments which had not been washed since they had last been used - washing iron instruments, of course, encouraged them to rust. Bleeding was stopped by cauterisation with a hot iron. Skull trephining (drilling a hole through the bone) was still performed to improve the "blood-brain balance".

been washed since they had last been used - washing iron instruments, of course, encouraged them to rust. Bleeding was stopped by cauterisation with a hot iron. Skull trephining (drilling a hole through the bone) was still performed to improve the "blood-brain balance".

Marie Colinet developed improved techniques for Caesarean section and was probably the first clinician to use a magnet to remove metal fragments from a patient's eye.

Read more about Colinet

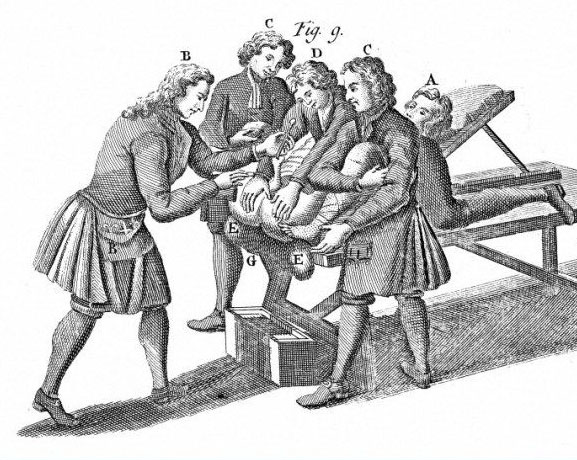

Urologically, this was the era of "travelling lithotomists" who toured the country removing bladder stones through incisions in the perineum without any form of anaesthesia (pictured). Lithotomists of this era included Thomas Hollier who, in 1662, operated on the diarist Samuel Pepys to remove his stone. Pepys was one of the lucky ones - few patients survived this procedure and those that did often suffered from incontinence due to sphincter damage and/or a urinary fistula.

← Back to Time Corridor